Introduction

The Gallic Wars, a war of conquest in Gaul waged by the Roman governor Julius Caesar . It began in 58 BCE and ended in 51 BCE. The Gallic Wars consisted of eight military expeditions and the result of the wars was the incorporation of Gaul into the Roman Republic.

The Gallic Wars were a turning point in the life of Julius Caesar, the result of which was to hasten the dissolution of the Roman Republic and the move towards empire. The war had a profound impact on the development of the Roman Republic, it stimulated the development of the slave economy and expanded the boundaries of Rome. At the same time the victory in the Gallic Wars brought great honour to Caesar.

Roman soldiers at the storming of Britain

Background

Gaul was a large area of land in the northern part of the Roman Republic, including contemporary northern Italy, France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, and parts of the Netherlands and Switzerland.

In the 1st century BC, the Roman republic was in crisis and the senators, led by Sulla, and the democrats, led by Marius and Cinna, fought to the death for power, with both sides fighting each other in retaliation and spilling blood in Italy. The result was that the Sullaists barely managed to keep the Senators in power, while the Marius faction, who were pushing for democratic reforms, were killed and wounded and fell into disarray.

Three new men emerged from the Roman political scene: Crassus, Caesar and Pompey. In 73 BC the great Spartacist revolt broke out and Crassus, a member of Sulla’s party, rose to power by putting down the Spartacist revolt. He was already the richest man in Rome by the time he was elected consul in 70 BC, and when he became consul he deliberately “cut blood” to win over the people, giving them a banquet of 10,000 tables and a three-month allowance of grain for all the Romans.

Julius Caesar, nephew of Marius and son-in-law of Cinna, was forced to wander during Sulla’s dictatorship. He returned to Rome only after Sulla’s death and was acclaimed for his accusations of corruption against the Sullaite governor of Macedonia, and became treasurer in 68 BC. He made a name for himself as the leader of the Marcionites and rose to social fame. Although he was from a famous family, his family was not rich and, given his generosity in order to win people over, he was in great debt. It is said that in 62 BC Caesar was offered a fat job as governor of Spain, but was unable to go because of his debts. At the same time, Pompey’s martial prowess was remarkable. In 70 BC he was elected consul together with Crassus. In 67 BC he purged the Mediterranean of the most rampant pirates and dealt a devastating blow to his enemies in the Third Mithradathian War (74-64 BC), when Mithradates fled to the Black Sea coast and committed suicide. The elimination of this formidable enemy, which had threatened Rome for decades, brought Pompey to prominence. However, some of the measures he took on his own initiative in the East were censured by the Senate.

Caesar had raided much during his time as governor of Spain. When he returned to Rome in 60 BC, he became even more ambitious and formalised a secret political agreement with Crassus and Pompey, forming what was known as the “Alliance of the First Three Heads”. According to this agreement, the three parties brought about Caesar’s election as consul in 59 BC, and during his term of office Caesar was required to try to approve the policies of Pompey in the East and to pass some bills in favour of the knights. All of these things were carried out by Caesar in spite of the opposition of the Senate, and his political popularity was greatly enhanced. In addition to his propaganda, he passed agrarian laws which gave land to 20,000 poor and childless citizens, instructed his cronies to campaign for the people, incited poor citizens against the senators, and distributed food to 3.2 million citizens free of charge during his tenure as tribune. These actions are a clear indication of Caesar’s ambition to gain supremacy by relying on the reputation of the people and the reformers.

But Caesar knew that if he was to overtake the other two, he would need to have a strong army and plenty of money, the greatest capital in the struggle. So he took a fancy to the governorship of Gaul and decided to go there when his consulship was over. He wanted to use the province of Gaul as a base from which to expand his territory, recruit troops, increase his strength and prestige and prepare the ground for greater power.

In 58 BC, by a three-headed agreement, Caesar became governor of Gaul for five years (58-54 BC), and in 56 BC he renewed the agreement for another five years. Caesar’s appointment as governor of Gaul marked the beginning of the Gallic Wars.

Eight expeditions

In 58 BC, Caesar became governor of southern Gaul and immediately expanded into northern Gaul. In 56 BC, Caesar conquered most of Gaul; in 55 BC, Caesar crossed the Rhine to attack Germania and tried unsuccessfully to enter Britain in the autumn of the same year; in 54 BC, Caesar attacked Britain again and, despite repeated victories, failed to take control; in 53 BC, Caesar suppressed a number of revolts in Gaul; in 52 BC, the tribes of Gaul, under the leadership of Vicentorius, started a great revolt, initially victorious, which was later suppressed by Caesar finally annexed all of Gaul in 51 BC.

The Gallic Wars included eight military expeditions. Caesar began his term of office with a major expansion.

The first expedition

took place in 58 BC, at the Battle of Byblast, when four of Caesar’s legions defeated the Helvetii, one of the most numerous Gallic tribes attempting to migrate south-west from the contemporary Swiss region.

The Second Expedition

In the same year, Caesar undertook his second expedition, defeating a coalition of Germanic tribes commanded by Ariovist, the chief of the Svef, and driving them across the Renus (Rhine).

The Third Expedition

In 57 BC, Julius Caesar launched his third expedition to conquer the Biel and other Gaulish tribes in the north-east. Thereafter, Caesar reported to the Senate that he had conquered all of Gaul.

The Roman plunder and atrocities provoked many uprisings by the Gallic tribes. To suppress these revolts, Caesar made five more expeditions against Gaul.

The Fourth Expedition

In 56 BC, Caesar made a fourth expedition to suppress the revolts of the Venetians and Aquedarians, defeating the rebels and persecuting them cruelly.

The Fifth Expedition

The following year, Caesar made a fifth expedition to Gaul, attacking the Venetians’ allies, the Germanic tribes of the Usipetes and the Tenketri, and crossed the Rhine to destroy them.

Britain

It so happened that Caesar, in the course of his expedition through Northern Gaul, discovered, through the mercenaries and travelling merchants who came to support the region, that there was another mysterious land across the sea from the Gallic Ministry. There were said to be rich tin deposits and unknown Shangwu tribes. But even the Gallic merchants knew little about what was going on there. To break up the Gaulish allies, Caesar was determined to go there to find out and try new conquests by force. Thus began the invasion of Britain by Caesar’s legions.

In the late summer of 55 B.C., Caesar began his first attempt to explore the island of Britain. He first ordered his men to take a ship with them to make a reconnaissance, and then with his entire army by his side he rushed to Morini, the nearest point in the strait. There he ordered that all the neighbouring regions should provide ships, and also that all the ships built the previous year to deal with the Gauls should be brought in with them.

The inhabitants of Britain belonged to a widely distributed Celtic population

The Britons were soon informed of Caesar’s intentions, which were not concealed by his thunder and lightning. Some tribes, compelled by Caesar’s prestige, sent emissaries offering to provide hostages and to follow Caesar’s orders. Many more, however, chose to resist to the end. In order to gain a foothold in Britain, Caesar agreed to the messengers’ request and sent his trusted Gaul, Camus, back with them to negotiate a covenant.

Only five days after their departure, the scouts sent out to scout returned with a general report of the situation on the other side. But, perhaps out of distrust or contempt for the Britons, Caesar did not wait for news of the messengers or the arrival of the following summer before arranging for the seventh and tenth legions to board the 80 transports. The rest of the ships were then allocated to cavalry and senior officers. Finally the remainder of the army was placed throughout Gaul to protect the rear.

Once everything was arranged, Caesar took advantage of a clear day to set off. It took less than a day for the first fleet to reach the coast of Britain. The narrow promontory and the mountains that rise up along the shore came into view of the Roman soldiers. Along with the natural landscape came the allied forces of Britain arrayed against the hills. It turned out that the Britons, having been informed of Caesar’s arrival, were determined to resist to the end. So they formed an alliance and arrested Caesar’s emissary, Commodus. When Caesar’s fleet appeared at sea level, the allied armies, already prepared, swarmed out in readiness to stop the enemy’s landing on the coast.

The Roman fleet

Although Caesar had made preparations for war, the landing site was so close to the mountains that spears could be thrown from the hills to reach the coast. Caesar therefore decided to wait until the rest of the fleet had arrived to rendezvous before looking for a landing place.

Soon most of the fleet had arrived, with the exception of the ships carrying the cavalry. Unwilling to wait any longer, Caesar called a military council. He informed the legion commanders of the current information and landing places and asked them to act quickly. After the meeting, the Roman fleet rushed to another beach 10 km away and prepared to land there. The unusually vigilant Britons also spotted Caesar’s intentions and arranged for cavalry and chariots to follow close behind, fearful of allowing the enemy to set foot on Britain.

Although the target shore was very open, the landing did not go well. Because the ships used to cross the sea could only anchor in deep water, the Roman heavy infantry had to wade through the water and face the lapping of the waves. This greatly hampered their speed of movement. To make matters worse, the lightly armed Britons also stood on the dry shore and threw javelins at the landing soldiers. There were even locals on warhorses who rode in and out to obstruct the Romans’ landing.

Seeing that the situation was critical, Caesar ordered his ships to move to the enemy’s flank. He then used the ship’s crossbows, archers and stone throwers to keep firing at the enemy on shore. With the fleet fire suppressing them, the British outposts were driven off the beachhead and retreated some distance away to regroup. But the soldiers were already demoralised by the foreseeable danger. In response, the flag-bearer of the Tenth Legion, who was in charge of the Eagle Flag, shouted: Jump down! Soldiers, unless you want your eagle flags to fall into the hands of the enemy! Then he charged the enemy with the eagle banner.

In the Roman army, the loss of an eagle flag was a great shame. Not only was it punishable, but it was also a loss of collective and individual honour. So the soldiers rushed forward to fight the enemy, regardless of the waves and the chaos of the scene.

Although they succeeded in arousing the soldiers’ spirit, the terrain still made the Romans confused. The disembarked soldiers even had difficulty finding their own ranks and had to follow their comrades around them. The soft beach and the constant lapping of the waves made it very difficult for them to even gain a foothold. The Britons had no such problems. They knew every dark beach and often drove their horses into it, surrounding Roman soldiers who were left alone. Large groups of men were constantly attacking the flanks of the Roman legions with javelins, making the situation dangerous again.

As the cavalry had not yet arrived, Caesar did not have the mobility to support the encircled soldiers and could not effectively cover the flanks. Fortunately, the battlefield was right on the sea and the Romans could use their boats for tactical manoeuvres. So Caesar ordered the soldiers still on board to board patrol boats and to move around to help.

As the Britons’ attack waned, the Romans regrouped and crossed the beach without incident. The British advantage was instantly lost and the legions suffered a crushing defeat in a frontal assault. Knowing that there was nothing more they could do to stop Caesar, the Britons again sent messengers to surrender. In addition to returning the Roman envoys they had seized, they also sent some hostages.

The Roman transports

On the fourth day after arriving in Britain, 18 transports carrying cavalry appeared on the sea. But just as Caesar was rejoicing over this, a sudden gust of wind blew them off the coast. It was also the night of the full moon when the sea suddenly rose and, with the lapping of the wind and waves, a large number of transports got stuck and collided with each other, some even being smashed to pieces. The Romans were completely helpless to stop this sudden natural disaster and did not even have the tools to repair it. Having lost their ships back to Gaul, they had to huddle in small camps and worry about the lack of provisions.

All this was seen by the Britons, who thus regained hope. Although they could not defeat the Romans, they could use the siege to force their lack of supplies into submission. So the Celtic tribes conspired with each other to stop giving hostages, and also to plan a surprise attack.

Although Caesar did not know what the enemy was up to, he could tell from the current situation that they would not remain subservient. So he arranged for his soldiers to intensify the collection of food from the neighbourhood and to dismantle the badly damaged ships to repair the less damaged ones. Soon the remaining ships, with the exception of the 12 lost, were back in service. Just as everything was being prepared, sentries reported the sighting of a large cloud of rising dust in the distance. The experienced Caesar immediately understood that this was an enemy attack on the Seventh Legion, which was gathering provisions. So he personally went to the rescue with the soldiers who were on duty.

By the time this blockade of reinforcements arrived, the soldiers collecting provisions had already suffered heavy losses. They were forced to huddle together and struggled to hold their line. The Britons, for their part, used their characteristic chariots and kept firing javelins at them from all around. When the thrown weapons were exhausted, the warriors in the vehicles would jump out and engage in foot combat. But even so, the Celts were unable to shake the Roman array. Frustrated, they chose to withdraw when they saw the arrival of reinforcements. Caesar, too, did not pursue them for lack of cavalry, and the two sides parted on bad terms.

Despite the limited results, the raid gave the Britons a boost in morale. They brought in more reinforcements, expecting a showdown with the Romans. As a result, the Britons were once again defeated without a hitch. In desperation, they again announced their surrender and promised to give up twice as many hostages as before.

Map of Britain in the 2nd century AD

As winter was approaching, Caesar hastily agreed to the proposal of the Britons, fearing further changes. Then, without even taking hostages, he led his entire army back to Gaul by ship.

The Sixth Expedition

Caesar was not satisfied with the results of his last expedition. So while he attended to the affairs of the Gallic dominions, he arranged for the soldiers resting in winter camp to hurry up the construction of ships suitable for the hydrographic conditions of Britain. Large quantities of supplies were also brought in from Spain for their use. Soon 600 transports and 28 warships were being built. Caesar transferred them to the port of Urs to join the previous year’s fleet.

In 54 BC, when everything was ready, he took 5 legions and 2,000 Gallic cavalry (20,000-25,000 men in total) on board ships and crossed the Straits of Lamanche, sailing again for Britain. Quite a few ships of non-military units followed the warship’s flotilla like a shadow, and they included many merchants and slave owners in private vessels, who, like sharks smelling blood, wanted a share of Caesar’s military victory.

Although a more favourable landing site was set, storms forced the Roman fleet to land again still at the same landing site as the previous year. The Britons, learning of Caesar’s return again, also assembled a large army. But when they discovered that this time the fleet was 800 ships strong, they again lost their nerve at once. They did not dare to stop them on the coast, as they had done in previous years, but chose a high ground to wait for them. So Caesar made it to the coast without incident and, having learned the enemy’s position, immediately rushed after them with four legions and 1,700 cavalry. The Romans managed to catch up with the enemy after a sharp march of about 18 kilometres in one go.

Gaulish cavalry serving in Caesar’s army

The Britons saw the Roman legions coming and sent cavalry to stop them at the river, only to be routed by the Gallic cavalry Caesar had brought with him. The men fled to the earthworks of the forest and fired a large number of thrown weapons at the Roman soldiers. The pursuing Seventh Legion also immediately set up a turtle shield formation to ward off the Celtic fire. Under their cover, the Roman army managed to build a wall that trapped the defenders in the fortifications. The fortress was soon breached and the Britons, who had fled in fear, escaped as night fell.

In the early hours of the following morning, the Romans rested and launched a three-pronged pursuit. Instead, they received orders from Caesar to recall them. Many ships had been damaged by another storm the night before and Caesar decided to fortify the camp and repair the ships. With these tasks completed, the Roman then proceeded once again to the fortress he had previously occupied. He was surprised to find that the Britons had organised a larger army than before, led by Cassivelanus, the leader of the Celtic Catuvelani tribe. The cavalry of both sides met and then engaged in a fierce battle at the outpost.

As the British cavalry were tactically backward and relied on the more primitive chariots, they were no match for the continental cavalry on the Roman side. So they chose the strategy of luring the enemy deeper, leading the Gaulish cavalry back into the woodland, which was unsuitable for cavalry fighting. Knowing this, Caesar asked the cavalry to retreat and not to pursue them further. Instead, the Britons launched a fresh counter-attack, charging out of the woods to attack the Roman legions who were building fortifications. By taking a loose succession of charge formations, the following troops could constantly support the front line. One of their attacks even reached the Roman legion’s flag, but Caesar arrived with his reserves and drove the Britannic troops away, but the Romans had already suffered a considerable number of casualties.

After this battle, Caesar was finally able to establish himself on the ground in Britain. Next he had to deal with the problem of supplies, and for this purpose three legions and all the cavalry were assigned to gather supplies.

After the unsuccessful assault, the Celtic strategy changed to using their familiar terrain and the mobility of their chariots to hold back the Roman army, waiting patiently for winter to come and crush the Romans in one fell swoop. Caesar, on the other hand, was in no position to stay long, so after a few rounds with the army of Caspianus, he decided to cross the Thames and attack the Celtic fortress directly.

And it was at this point that Caesar was given the perfect opportunity to provoke the infighting of the Britannia Celts, which became the decisive turning point in the Second Britannia Expedition.

The Catuvelani tribe was the most powerful in all of Britannia, and their leader, Cassivelanus, was an outstanding military leader, but his own ability in diplomacy and his tactics in uniting a united front were poor, causing discord among the major tribes. He himself was irascible and dealt with conflicts simply and cruelly. A disagreement over strategy led to his execution of the chief of the Trinovent tribe in eastern Britannia. When the young prince Mendubrasius heard that his father had been killed by Casvilanus, he fled to Caesar and the Romans, and his people surrendered to Caesar in return for the latter’s help against Casvilanus and the return of Mendubrasius to the throne.

Caesar, of course, graciously accepted their terms. Soon another smaller Celtic tribe was defeated and the allied lines began to gradually disintegrate. Caesar seized this opportunity to launch a general attack, during which the Celtic traitors betrayed information about the last stronghold of Casvillanus and the location of the crossing point across the Thames. Caesar then ordered his cavalry to open up the road and attacked at any cost. The Celts, who had been on the other side of the river, were clearly overwhelmed by the Roman momentum and after a brief exchange of blows abandoned the river bank and retreated backwards.

The Roman army burned fields and farms and houses along the way to prevent ambushes, and the strength of the army caused the tribes along the way to surrender. Catuvelanus had sent letters to the four chiefs of the Kentish region asking them to attack Caesar’s beachhead position to relieve the siege, but the plan failed. Catuvelani’s fortress, though fortified by natural barriers, was unable to withstand Caesar’s attack, and Casiviranus led the remnants of his army away from the other end of the fortress, leaving a large population and livestock as Roman spoils of war.

Eventually, the desperate Casvilanus had to surrender and Caesar made him hand over some hostages and promise to pay an annual tribute to Rome. At the same time, Caesar fulfilled his promise to the tribe of Trinovantes by helping Mendobrasius to become the new tribe’s leader and ordering Casiviranus not to harm the tribe, so that Trinovantes became the first Britannic tribe to be protected by the Romans.

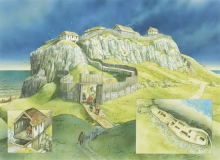

The High Mountain Fortress of the British Celts

In view of the sudden outbreak of rebellion in Gaul, Caesar then accepted the submission of the other side and returned to Gaul after being given hostages.

The Britons were not immediately brought under Roman rule The Britons suffered a crushing military defeat but remained de facto independent thanks to the Gallic rebellion and the Roman civil war that followed. Caesar was then too busy crisscrossing the Mediterranean to return again. The generations of rulers who followed him also lacked enthusiasm for conquest in this remote region. It was not until more than 90 years later that Emperor Claudius conquered Britain again.

The Seventh Expedition

It took place between 54 and 53 BC to suppress uprisings by the Eburones, Aduatiki, Nervii, Treveri and other tribes.

The last expedition

took place in 52 BC to suppress an uprising involving almost all the Gallic tribes led by the outstanding military chief, the Avernian tribal chief Vercingetoli. The insurgents defeated the Romans at Gogovia (near present-day Clermont-Ferrand) (Battle of Germovia). However, due to Caesar’s sowing of dissension and strife between the tribes, the main body of the Vicintoli was surrounded by the Roman army at the fortress of Alesia. Caesar’s army defeated the Vicentorian reinforcements at the Battle of Alesia, forcing the garrison to surrender. Caesar then led his army to crush a number of revolts by Gallic tribes in 51 BC. A feature of Caesar’s wars in Gaul was the brutal massacres and rapacious plundering of the defeated.

Reasons for victory

Caesar’s wars against Gaul were won for two main reasons.

Firstly, the Roman army had the advantage in terms of men and technical equipment. Rome was a developed slave state with a high economic level and a well qualified and experienced army that had been fighting for many years. The Gaulish tribes, on the other hand, were at the end of primitive society, had not formed a state, were mainly nomadic, were economically very backward and had a poorly qualified and equipped army. As a result, the Roman armies were usually able to defeat the tribes and regions at a more rudimentary stage of social development in the course of their expansion.

Secondly, Caesar himself was wise and brave, and had a correct strategy and tactics and a strategic plan. Militarily, he was good at thorough reconnaissance of the enemy and the terrain, was not confined to a single method of warfare, used flexible and varied methods of warfare, acted decisively and with determination, was good at using favourable terrain and quickly constructing fortifications, was good at rapid manoeuvring of forces and carrying out sudden strikes, and once he had defeated the enemy, he was sure to follow him up and win by total annihilation. Therefore, this is an offensive annihilation strategy characterised by aggressive, bold action and the annihilation of the enemy’s living forces. At the same time, in order to isolate and divide the enemy, Caesar focused on diplomacy, using tactics and ploys to divide the numerically superior but disunited tribes.

The victory of the Gallic Wars had far-reaching consequences for the Roman Republic. The influx of slaves and wealth into Rome stimulated the development of the Roman slave economy, and the rich Gaulish region became part of Rome’s territory, extending it to the west bank of the Rhine and east of the Pyrenees, and as far as Britain.

Commentary

Caesar’s victory in the Gallic Wars brought him great honour and provided him with a sufficient basis for his dominance and power in Roman politics. Caesar marched on Gaul with only four legions (one of which had originally belonged to Pompey). The opponents he had to conquer were not the decaying ancient nations of the East, but “the barbarous, uncivilised Gauls and Germans, who were able to fight. These people were so united and determined in their struggle for freedom and in maintaining their old reputation for valour and warfare that all threw themselves wholeheartedly into the war against the Romans.” Faced with such a formidable opponent, Caesar waged war by employing a strategy of dividing and dismantling, drawing in blows, intimidating and intimidating, and devouring at every step. “He called the leaders of the tribes to himself” and either “intimidated” or “encouraged”, “bribed “to intimidate” or “encourage”, “buy”, “divide”, and “make the Gauls finally loyal to him. Those who openly rebelled against him were slaughtered in a frenzy, even treacherously killing innocent people in war. During his seven years in Gaul, Caesar continued to recruit and expand his army. By the time of his triumph in Rome, he had a large army of 10 legions loyal to him. Caesar’s conquests and plundering of Gaul brought great havoc to the local people. According to Plutarch: during his seven years of campaign, Caesar raided and captured over 800 cities, conquered over 300 tribes and fought against a total of three million Gauls, of whom one million were annihilated and one million were taken prisoner. This, of course, must have provoked strong resentment among the people of the conquered areas. As a result, throughout the Gallic Wars, there was a constant struggle against the people of the various regions. The Gauls were brave and courageous. They took advantage of their familiarity with the terrain and used very flexible strategic tactics, either by “striking from the east”, “cutting off supplies”, “surprise attacks”, or The Roman army was dealt a heavy blow by the “internal and external attack” …… and many heroic feats were performed. The Romans also marvelled that “they were some brave men”.

However, the Gauls faced the conquest of the Roman army without forming a united army against the enemy and lacked unity of command and deployment. As a result, they were unable to work together and were defeated by the Roman army, especially in the face of the usual Roman tactics of “bribery”. At the critical moment of the Vicentorius revolt, the Gauls did not take Vicentorius’ advice and organise all the Gauls who could fight to the death against the Roman army. Instead, only a limited number of troops were drafted in to rescue the insurgents. As the reinforcements rushed to the city, the insurgents did not break out in time, thus depriving the Gauls of a valuable opportunity to fight and failing the breakout. The Roman army won a decisive victory.